DOI: https://doi.org/10.46502/issn.1856-7576/2024.18.03.16

Cómo citar:

Bilichenko, A., Martynenko, N., Derevianko, L., Mizina, O., & Iatsyna, M. (2024). The effectiveness of interactive online courses for the speech competence development in non-language-major students. Revista Eduweb, 18(3), 204-222. https://doi.org/10.46502/issn.1856-7576/2024.18.03.16

The effectiveness of interactive online courses for the speech competence development in non-language-major students

Eficacia de los cursos interactivos en línea para el desarrollo de la competencia lingüística en estudiantes no licenciados en idiomas

Alla Bilichenko

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1569-3834

Bila Tserkva National Agrarian University, Bila Tserkva, Ukraine.

Nadiia Martynenko

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5695-4685

Flight Academy of the National Aviation University, Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine.

Liudmyla Derevianko

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6271-6571

National University “Yuri Kondratyuk Poltava Polytechnic”, Poltava, Ukraine.

Olha Mizina

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1988-6353

National University “Yuri Kondratyuk Poltava Polytechnic”, Poltava, Ukraine.

Maksym Iatsyna

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5512-5378

Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine.

Recibido: 01/08/24

Aceptado: 28/09/24

Abstract

Interactive online courses are becoming increasingly popular among students studying foreign languages. The aim of the article is to analyse the effectiveness of interactive online courses in the speech competence development of non-language-major students. Research methods included student surveys, testing before and after the interactive online courses, mathematical statistics methods (t-test, Likert scale). The testing showed a significant improvement in the results of the experimental group (EG) that studied using interactive online courses (B2 – 43.5% of students, C1 – 21.7%, C2 – 21.7%). Online courses were found to provide valuable opportunities for real language practice with an average score of 3.6. The user interface and features were found to be user-friendly and easy to navigate, with an average score of 3.5. The variety of topics covered in the interactive online courses was identified as beneficial for general language skills, with an average score of 3.6. Flexibility in study planning was consistent with the benefits, receiving a high mean score of 3.8. The practical value of these results is their ability to improve the practice of foreign language learning. The results provide important insights into the effectiveness of interactive online courses.

Keywords: Interactive methods, learning efficiency, speaking competence, online courses, immersive learning, non-linguistic majors.

Resumen

Los cursos interactivos en línea son cada vez más populares entre los estudiantes de lenguas extranjeras. El objetivo de este artículo es analizar la eficacia de los cursos interactivos en línea en el desarrollo de las competencias lingüísticas de los estudiantes no licenciados en idiomas. Los métodos de investigación incluyeron encuestas a los estudiantes, pruebas antes y después de los cursos interactivos en línea, métodos estadísticos matemáticos (prueba t, escala de Likert). Las pruebas mostraron una mejora significativa en los resultados del grupo experimental (GE) que estudió utilizando cursos interactivos en línea (B2 - 43,5% de los estudiantes, C1 - 21,7%, C2 - 21,7%). Se comprobó que los cursos en línea ofrecían valiosas oportunidades para la práctica real del idioma, con una puntuación media de 3,6. La interfaz de usuario y las funciones resultaron fáciles de usar y navegar, con una puntuación media de 3,5. La variedad de temas tratados en los cursos interactivos en línea se consideró beneficiosa para las competencias lingüísticas generales, con una puntuación media de 3,6. La flexibilidad en la planificación del estudio fue coherente con los beneficios, recibiendo una alta puntuación media de 3,8. El valor práctico de estos resultados es su capacidad para mejorar la práctica del aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras. Los resultados aportan información importante sobre la eficacia de los cursos interactivos en línea.

Palabras clave: Métodos interactivos, eficacia del aprendizaje, competencia oral, cursos en línea, aprendizaje inmersivo, carreras no lingüísticas.

Introduction

Innovative technologies are radically changing the education system, primarily the field of teaching English in universities in the modern world. Global issues and challenges related to this process have important implications for the educational system as a whole (Tursunovich, 2022). Digital transformation in higher education is becoming an integral part of the learning process, providing both new opportunities and serious challenges. The studies show that the integration of technology in education requires not only technical readiness, but also changes in approaches to learning and perception of the learning process (Baidoo-Anu & Ansah, 2023).

One of the key challenges is the need to adapt traditional teaching methods to the possibilities of modern technologies. The use of interactive online platforms, web conferencing, e-learning materials and educational programmes is becoming an integral part of the learning process (Gopal et al., 2021). However, the successful integration of these technologies requires not only the technical competence of teachers, but also a change in the pedagogical approach (Crawford et al., 2020). Changes in teaching methods involve a transition from the traditional lecture format to a more interactive, active communication of students. Research also emphasizes the need to ensure accessibility and inclusiveness of education when using technology (Rojabi, 2020). This requires not only updating the technical resources of universities, but also training teachers in new teaching methods with a view to modern educational technologies (Tinh et al., 2021).

An important aspect is also the assessment of the effectiveness of new teaching methods using technology. The use of online tools implies changes in the system of assessment and control of knowledge. Educators and institutions need to develop effective assessment methods that take into account the features of distance learning and digital technologies (Zhou et al., 2020). Universities around the world have a diversity of students from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. This creates challenges for effective learning (Zhylin et al. 2023). The development of strategies that facilitate adaptation to a multilingual and multicultural context becomes a key issue. In the current conditions of globalization and world trends in the development of education, universities face complex challenges related to the provision of educational services at the global level. This process requires educational institutions to develop flexible strategies that can adapt to the diversity of students and meet the modern requirements of the global labour market (Sari & Wahyudin, 2019).

The globalization of education leads to an increasing number of students from different countries, with different cultural and linguistic backgrounds in universities. This requires the implementation of personalized educational strategies that take into account the students’ diverse needs and learning preferences. The teaching staff and curricula must be able to effectively interact with such a diverse student population, requiring the development of methods that promote inclusion and adaptation (Gunawan et al., 2020). Global changes in the economy and technology affect the needs of the labour market. Universities must adapt their curricula in such a way that graduates possess not only language skills, but also competencies that are in demand around the world. This includes the development of communication skills, critical thinking, intercultural competence and teamwork skills (Albashtawi & Al Bataineh, 2020). According to the studies, today’s students expect not only language skills from a university education, but also the development of skills necessary for a successful career. Curricula should effectively integrate language learning with the development of key competencies (Albiladi & Alshareef, 2019).

The main prerequisite for successful adaptation of universities to changes related to technological transformation is the level of technology readiness of teachers and students. The quality of learning and interaction in the learning environment depends on how effectively they are able to use modern educational technologies (Coman et al., 2020). A lack of technological literacy can hinder the successful integration of digital tools into the learning process. Therefore, there is a need for systematic education and training of teachers, as well as support for students in mastering new technologies for their maximum use for educational purposes.

Successful preparation of students to work in a multilingual and multicultural environment is becoming increasingly important in the context of globalization. University graduates must not only have excellent language skills, but also be prepared to communicate with people from different cultures and understand different work styles and values. This requires the development of educational programmes that include the use of interactive online courses and an emphasis on the development of soft skills such as communication, adaptability, and cultural awareness (Gustanti & Ayu, 2021). This paper addresses the gaps in earlier studies, presents a new perspective, and aims to contribute to the development of knowledge in the field of English language teaching.

The aim of the research is to study the effectiveness of interactive online courses for the development of speech competence in non-language-major students.

Research objectives:

The use of interactive online language learning courses has gained momentum across various disciplines due to their adaptability, flexibility, and ability to cater to diverse learning needs. These courses provide learners with access to personalized instruction, real-time feedback, and opportunities to engage in language practice in ways that traditional classroom settings might not offer. While interactive online courses have proven to be effective in language programs, less is known about their impact on students in non-language majors. Such students, who often lack extensive exposure to language learning, may benefit from tailored approaches that focus on developing their speech competence. This gap in research provides the foundation for the current study.

Rationale for the Study

Investigating the effectiveness of interactive online courses for non-language majors is important for several reasons. First, non-language majors typically do not receive extensive language training as part of their curriculum, which may lead to limited opportunities for developing speech competence. Yet, in today's globalized and interconnected world, communication skills are critical, regardless of the academic or professional field. Second, non-language students may approach language learning differently from their peers in language-focused programs, presenting unique challenges and learning needs. Understanding how interactive online courses can address these specific needs is essential for improving educational strategies in non-language disciplines.

Article Structure

The article is divided into several sections.

By focusing on how interactive online courses can support non-language-major students in speech development, this study aims to contribute valuable knowledge to the evolving field of technology-enhanced education.

Literature Review

Research in the field of English language teaching in universities focuses on adaptation to changes caused by the informatization process. The following common trends are observed in world literature: the use of technologies in the educational process, the introduction of online platforms and electronic resources in education. In the USA, Great Britain and other developed countries, much attention is paid to the integration of technology into the educational process to improve the quality of education. Research in these countries ranges from the use of interactive learning platforms to the development of new learning formats (La Velle et al., 2020). The situation is, however, more diverse in the context of developing countries.

Some of these countries are actively implementing distance learning and extensively use online platforms to improve access to education and overcome geographic barriers. This is especially relevant where the level of technological readiness of society enables the use of modern educational innovations (Goksu, 2021). On the other hand, some countries face limitations such as insufficient technological infrastructure, limited Internet access, and cultural differences. In these cases, the introduction of new methodologies and technologies may be slower, and the transformation of educational practices requires additional efforts and adaptations.

Conflicts in the field of English language teaching in universities can be manifested in the issues of effective integration of technologies in the educational process. Some researchers and educators may emphasize the use of modern learning tools such as interactive online platforms, virtual classrooms, and mobile applications as means of actively engaging students (Kasneci et al., 2023). Others may follow traditional methods, emphasizing the importance of personal interaction and classroom learning. These contradictions may raise issues of effectiveness, accessibility and teacher preparation for the use of modern technologies in teaching English (Lapitan et al., 2021). Another aspect of the conflict is the issue of maintaining a balance between traditional and modern teaching methods (Simanjuntak et al., 2022).

Another aspect of the conflict is the understanding of the role of language learning in the context of informatization and its impact on the quality of students’ communication. Some researchers may focus on the development of language skills through technological tools, while others may question the effectiveness of electronic tools in achieving high levels of communication skills. Conflicts can arise when evaluating the impact of technology on improving or weakening students’ language and communication competence (Murray & Christison, 2019). One of the identified gaps in research on adaptation to changes in the informatization of university education is insufficient attention to cultural and linguistic aspects. In particular, there is a risk of insufficient inclusion of intercultural aspects in the development and implementation of new technologies in the learning process (Dewaele et al., 2019). This gap can lead to an underestimation of the cultural context of students and teachers, which can affect the effectiveness of educational programmes and tools in different cultural environments.

Another limitation may be the limited understanding of how information-related changes affect students with different levels of language proficiency. Research may remain insufficient to analyse how technological changes affect the language skills, learning characteristics, and communication abilities of different groups of students. This limitation can reduce the generalizability of the results and make it difficult to develop approaches that are specifically targeted to the needs of different language groups (Nartiningrum & Nugroho, 2020).

The researchers analysed the impact of different types of communication on student motivation and satisfaction in the context of online language learning (Bailey et al., 2021). The results showed that synchronous communication, such as video conferencing and real-time chats, facilitates a greater level of interaction between students and teachers. This increases their internal motivation and satisfaction with the learning process. Students noted that the possibility of immediate feedback and active participation in discussions creates a sense of community and increases engagement in the learning process.

An additional limitation may arise from the limited scope of new methodologies and technologies that may not cover all aspects of language teaching. In some cases, research may focus on specific innovations without fully understanding their implications for different aspects of language education. This can complicate the development of universal adaptation strategies and limit the applicability of research findings in different educational contexts (Macaro et al., 2018). Addressing these limitations requires a deeper analysis of cultural and linguistic factors in the development and implementation of technologies, as well as taking into account the individual characteristics of students with different language skills and cultural backgrounds.

Methods and Materials

This study utilized a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative data to evaluate the effectiveness of interactive online courses in improving the speech competence of non-language-major students. The research was designed to comprehensively assess the progression of students' language skills, with an emphasis on pronunciation, fluency, and comprehension. Both experimental and control groups were utilized to ensure a comparative analysis of online versus traditional learning environments. A variety of data collection methods, including standardized tests, student surveys, and progress monitoring, were employed throughout the study. The use of multiple online platforms enabled the research to gather data on diverse teaching methods and their impact on speech competence development.

Research design

Empirical research was conducted in several stages. The first stage involved the selection of non-language-major students from different universities. The second stage provided for preliminary testing to assess the initial level of students’ speech competence. The third stage is training based on interactive online courses in the EG and traditional offline classes in the control group (CG). At the fourth stage, students’ progress was monitored. The fifth stage is final testing: after the course was completed, all students re-passed the same standardized test as at the beginning of the study. The sixth stage is data analysis.

So, the research design was carefully planned and implemented to ensure reliable and valid results. The study lasted one academic semester (4 months). The following interactive platforms with online courses for learning English were chosen for its implementation in the EG:

Duolingo is a popular free English language learning platform that uses interactive lessons and groups of exercises to engage students in learning (Figure 1). This will allow us to evaluate the effectiveness of online courses on a large amount of data.

Figure 1. An example of the Duolingo interface and tasks

Rosetta Stone uses an immersive learning method built on visual and audio methods without the use of translation (Figure 2). This platform can help in researching the impact of the immersion approach on language learning outcomes among students, which can be valuable information for our research.

Figure 2. Course example from Rosetta Stone

Coursera offers English language courses from universities around the world, including different teaching methods (Figure 3). This platform will allow us to evaluate the impact of academic approaches to English language learning, which can be useful for analysing the effectiveness of courses at the higher education level.

Figure 3. Course example from Coursera

Udemy is an online course platform where educators can create and deliver their own courses (Figure 4). This provides an opportunity to explore a variety of teaching methods and assess the impact of different approaches on student learning outcomes.

Figure 4. Example of courses from Udemy

The selected platforms provided an opportunity to collect data on their effectiveness in the context of our research on interactive online English language courses.

Sample

To study the effectiveness of interactive online courses for the development of speaking competence, a representative sample of students from 4 Ukrainian universities (Bila Tserkva National Agrarian University, National Aviation University, Yuri Kondratyuk Poltava Polytechnic National University, Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University) was selected. The sample included 345 undergraduate non-language-major students aged 19 to 25 studying Software Engineering, Economics, Aviation Transport, Law. Such a number of participants ensures high statistical significance of the results, which allows more accurate detection of differences between the EG and CG and reduces the probability of random errors. The choice of majors provides a variety of academic areas, which enables to study the effectiveness of interactive online courses in the context of different fields of knowledge and increases the overall representativeness of the study. Therefore, the selection criteria included: age, study in one of the indicated non-language major, basic level of English language proficiency. All students voluntarily agreed to participate in the study and signed an informed consent.

The training was conducted by 4 teachers from the language departments of the mentioned universities. The sample was randomly divided into two groups: the EG and the CG — 132 and 133 students, respectively. The distribution of students was carried out using the randomization method, which ensured an even distribution by gender, age and initial level of speech competence. The EG students completed a course of interactive online classes designed specifically for the development of speaking competence. The CG students continued their studies according to the traditional method, which included offline classes with a teacher according to the standard curriculum.

Before starting the study, all participants were pre-tested to determine their initial level of speech competence. This made it possible to compare the results before and after taking the courses and evaluate the effectiveness of different teaching methods.

Research methods

The methodology used to evaluate the effectiveness of teaching English language students corresponded to the experimental design. The data were collected using pre-and post-tests on the level of spoken language proficiency in each group. They were conducted in the form of an Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI). This is a face-to-face interview between the student and the examiner via video conference. The examiner asked questions related to various aspects of language during the interview. The principles of reliability and competence were followed when collecting data. Student responses were evaluated based on criteria such as vocabulary use, grammatical accuracy, speaking speed, pronunciation, and coherence.

Questions of the Oral Proficiency Interview

The level of spoken language proficiency was assessed according to the standardized scale of The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), which ranges from A1 (Beginner) to C2 (Proficient). The content validity of the tests was checked during discussions with university professors included in the study. The discussion was held by e-mail. The final form of the questions was established after reaching agreement among all participants regarding the completeness of the coverage of the questions, the problems being studied, and the respondents’ attitude to them. The survey was conducted online in Google Forms, which was sent to students by e-mail.

The methods of mathematical statistics: t-test (to assess the significant difference in results before and after using interactive online courses), Likert scale (to collect data by measuring the degree of agreement or disagreement of respondents with the statements on the scale).

Instruments

The tool for evaluating the students’ experience working with the selected technologies was a 5-point Likert-type rating system, the points of which are distributed as follows: (1) “Strongly disagree”, (2) “Disagree”, (3) “Neutral”, (4) “Agree” and (5) “Strongly Agree”. The reliability of the survey was tested using Cronbach’s alpha. The obtained result α = 0.769 gives grounds to assess the internal consistency of the survey as sufficient for the study. Quantitative data were collected and calculated using the SPSS 26 computing tool. The effectiveness of the proposed model was studied using a t-test and the sample standard deviation to rule out differences between group surveys. The mean score of each Likert scale item was calculated to quantitatively analyse these data.

This study adopted a mixed-methods research design, combining both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of interactive online courses on speech competence development in non-language-major students. The quantitative component involved pre-and post-test scores from standardized speech proficiency tests, specifically the Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI), and statistical analysis of the improvements in the experimental and control groups. The qualitative component included student surveys and feedback that offered insights into their learning experiences. The choice of a mixed-methods approach was justified by the need to capture both measurable changes in performance and the subjective learning experiences of students, providing a holistic view of the effectiveness of online learning.

Implementation of Online Courses

The interactive online courses in the experimental group were implemented over the course of one academic semester, which lasted four months. Students engaged in sessions for a duration of three hours per week, divided into two 90-minute sessions. Each online platform—Duolingo, Rosetta Stone, Coursera, and Udemy—was used in rotation to expose students to varied teaching methods and learning experiences. Duolingo was employed for interactive exercises, Rosetta Stone for immersive learning, Coursera for academic-style instruction, and Udemy for customized lessons. The integration of these platforms ensured a balanced and comprehensive approach to language learning, focusing on different aspects of speech competence, such as fluency, pronunciation, and comprehension.

Validity of Instruments

The Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI), a widely recognized standardized test for evaluating speech competence, was selected for pre-and post-test assessments due to its reliability and validity in measuring various aspects of speech proficiency. The OPI has been extensively validated in prior studies, particularly in assessing spoken language development in diverse educational contexts. Additionally, the surveys used to gather qualitative data were developed based on previously validated instruments, ensuring they accurately measured students’ perceptions of their learning experiences and engagement.

Random Assignment of Participants

Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (EG) or the control group (CG) using a computer-generated random number system. This randomization process ensured that each group was comparable in terms of initial language proficiency, background, and demographic factors. Stratified random sampling was also used to balance gender and academic background across both groups, further ensuring that the results were not influenced by demographic variables.

Control of External Variables

To ensure that external variables did not affect the outcomes, several control measures were implemented. The study controlled for prior language exposure, student motivation levels, and access to learning resources by administering preliminary surveys and adjusting for any significant differences through statistical methods such as covariance analysis (ANCOVA). Additionally, all students had access to the same technological tools (computers and stable internet) to avoid discrepancies caused by resource availability.

Ethical Considerations

The study adhered to strict ethical guidelines. All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study, with the purpose, procedures, and potential risks of the research clearly explained. Students were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. The data collected were anonymized to protect participants’ privacy, and the study received approval from the university’s ethics committee.

Control Group Structure

The control group received traditional offline instruction, which consisted of lectures, in-class discussions, and face-to-face interactions with teachers. The course content was identical to the online courses but delivered in a conventional classroom setting. The frequency and duration of lessons matched the experimental group, with three hours of instruction per week spread over two 90-minute sessions. This allowed for a direct comparison between the interactive online course structure and the traditional offline methods, highlighting the impact of delivery mode on speech competence development.

Results

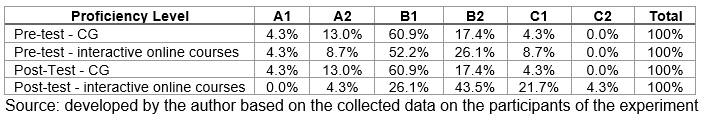

The results of the pre-and post-tests showed the following percentage data (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of pre-and post-tests

The stage of preliminary testing involved the CG participants with different levels of language proficiency. The distribution of language proficiency levels in the CG was as follows: 4.3% — at the A1 (Beginner) level, 13.0% — at the A2 (Elementary) level, 60.9% — at the B1 (Intermediate) level, 17.4% — at the B2 (Upper-Intermediate) level, and 4.3% — at the C1 (Advanced) level. None of the CG participants achieved the highest qualification level C2 (Proficient).

In the EG, which used interactive online courses in education, the distribution of language proficiency levels on the previous test was as follows: 4.3% were at the A1 level, 8.7% — at the A2 level, 52.2% — at the B1 level. 26.1% were at the B2 level, 8.7% were at the C1 level, and no participant reached the C2 level.

This information provides an overview of the initial levels of language proficiency of the participants in each group prior to the use of different language practice methods. Most of the CG students (60.9%) had B1 (Intermediate) level. This shows that the students in this group discussed common, everyday topics and had basic conversations in English. The EG: the highest percentage (52.2%) of students in this group had B1 (Intermediate) level. The higher percentage of students with the B2 (Upper Intermediate) level (26.1%) indicates that they could engage in more complex conversations or discuss a wider range of topics.

Post-test indicators in the CG and EG are presented in Fig. 5. The percentage distribution of proficiency levels in the CG remained relatively constant in the post-test compared to the pre-test. This indicates that there was no significant improvement in the level of spoken language in the CG during the study.

These results provide insight into the effectiveness of different methods. It is evident that there was a higher percentage of participants with higher levels of language proficiency (B2 and C1) compared to the CG due to the use of interactive online platforms (EG). This suggests that interactive online platforms were useful for improving the speech competence of non-language-major students. These results are based on the assumption that higher proficiency levels (B2 and C1) reflect improvement, while lower levels (A1 and A2) may indicate problems requiring attention.

Testing showed a significant improvement in the EG results group. This shows that the use of interactive online courses was found to be more effective in improving students’ speech competence than traditional methods. The sample standard deviation (s) is approximately 0.45. A t value of approximately 13249 indicates a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores for the interactive online courses (EG). In a paired t-test, the t value measures the size of the difference relative to variability within the sample. The higher the t value, the more likely it is that the observed difference is not caused by the chance alone. In this case, a t value of 13249 suggests that the difference between pre-test and post-test scores is very significant and unlikely to be explained by random variation. It is important to note that the negative percentages (≈−50.0% and −−16.7%) predict a decrease in the percentage of students at the B1 (average) level after the experiment in both groups. This may be related to the transition of students to higher levels of language proficiency (B2, C1, etc.), and not to a decrease in the general level of language proficiency.

Table 2 presents the results of evaluation of interactive online courses by students on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 2.

Results of evaluation of interactive online courses by students (on a 5-point Likert scale)

An evaluation of interactive online courses compared to traditional learning revealed several key findings. First, they were effective in providing valuable opportunities for real language practice, with 75% of students agreeing. Special attention was paid to interaction with native speakers, which 50% of participants consider useful for improving speaking competence. Furthermore, the platform’s user-friendly interface and features with interactive online platforms were positively perceived by 65% of students, contributing to their overall satisfaction. A total of 65% of students appreciated the variety of topics covered in online courses. Besides, the flexibility of lesson planning corresponded to the preferences of the majority (80%) of the participants. The mean score of each Likert scale item was calculated to quantitatively analyse these data (Table 3).

Table 3.

Average score of each Likert scale item

So, interactive online courses have their strengths: useful in real language practice, flexible schedule, and development of speech competence. Positive student feedback was received consistent with the OPI results. Improvements may include addressing the discomfort some students experience with providing feedback during traditional learning and improving the usability of interactive online platforms.

The interactive online courses proved to be more effective in improving the speech competence of non-language-major students compared to traditional offline methods. Several specific mechanisms likely contributed to this observed improvement:

The quantitative data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the pre-and post-test scores of both the experimental and control groups. Significance levels (p-values) were set at 0.05, indicating that a difference between groups was considered statistically significant if the p-value was less than 0.05. The results showed that the experimental group demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in speech competence over the control group, with a p-value of 0.001, confirming that the interactive online courses had a stronger positive impact than traditional instruction. Additionally, effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d to measure the magnitude of the difference between the groups. The effect size was 0.85, indicating a large effect according to conventional benchmarks, further supporting the superior efficacy of the online courses. Post-hoc analysis revealed that the experimental group improved more significantly in key areas such as pronunciation and fluency, where traditional teaching methods showed more modest gains. The results suggest that the immediacy of feedback and flexibility in the online courses contributed to these gains.

Discussion

The results of the study indicate the effectiveness of interactive online courses in improving students’ speech competence. This shows the wide recognition and acceptance of online courses, which is proven not only in our study, but also in previous research. Duolingo’s focus on pronunciation and its gamified approach to language learning make it attractive to students who want to learn effectively and have fun (Nelson & Bonnac, 2022). Our study notes a difference in the degree of popularity of digital platforms compared to previous studies where these platforms may have had higher ratings. This emphasizes that the chosen platforms may vary in popularity depending on the specific context and student needs (Novita, 2021).

One of the studies shows that individual differences in student preferences may be related to comfort levels with particular platforms and learning methods (Kasneci et al., 2023). This indicates the need to support individual choice and consider the diversity of approaches to learning in higher education (Ali & Abdalgane, 2022). Our research supports this finding, showing that the effectiveness of interactive online courses depends to a large extent on the ability of these platforms to take into account the students’ individual needs and preferences. For example, some students may respond better to the gamified elements of Duolingo, while others may benefit more from structured academic courses on Coursera. The multi-approach platforms such as Rosetta Stone and Babbel are used for a more personalized learning experience that promotes speech competence.

General agreement with the conclusions about the high popularity of interactive online courses confirms the trends of digital education. These courses take an important place in student selection, reflecting generally accepted standards for using digital tools for learning and self-development (Kubaczka & Polok, 2023). Despite the differences in the selection of individual online courses, their lower popularity does not necessarily indicate the ineffectiveness of these platforms. Differences may be related to the context of use and the students’ individual needs. The variety of platform choices points to the need to consider context and individual preferences when choosing digital learning tools (La Velle et al., 2020). It is important to understand that the choice of digital platforms is complex and depends on the specific environment in which they are used.

Differences in the choice may be determined by the specifics of the course, the structure of the study and the students’ personal preferences. This emphasizes the importance of individualization and flexibility of the digital learning system. The opportunity to choose the right tools provides optimal conditions for each student. Active use of online courses for various assignments and tests is a standard practice among teachers (González‐Lloret, 2020). This creates an interactive learning environment that engages students in the learning process. Our research found that interactive elements such as video lessons, language games, and dialogue exercises not only increase student engagement, but also improve their speaking skills. Online platforms such as Duolingo, Babbel, and EF English Live allow students to actively interact with the learning material, which promotes deeper assimilation of knowledge and skill development. So, our results demonstrate that the use of interactive online courses can be an effective tool for improving students’ speech competence. They confirm that interactive learning methods, which are widely used by teachers, create a favourable environment for student engagement and increased learning efficiency.

The results of the earlier study reveal that students show a higher level of satisfaction and motivation when using synchronous communication methods (video conferencing and real-time chats) (Bailey et al., 2021). Our research also found that interactive elements provide feedback, significantly increase the effectiveness of training. Accordingly, both studies emphasize the importance of interactive and engaging learning methods for improving students’ speaking skills, which confirms the feasibility of using interactive online courses for this purpose.

The use of digital resources allows teachers to diversify tasks and create interactive scenarios for students (Goksu, 2021). This strengthens the relationship between the teacher and students, as well as intensify the educational process (Sari, 2020). A comparison of the results with similar studies identifies both similarities and differences in the level of improvement in students’ speech competence. This indicates the need for flexibility in the integration of interactive online courses in language learning, taking into account the students’ diverse needs and preferences of. The obtained results confirm the achievement of the determined aim and objectives of our research. Practical use implies improving English language training programmes among non-language-major students. Educational institutions and educators can integrate interactive online courses such as Duolingo, Babbel, Coursera, EF English Live and Udemy into their curricula to create a more effective learning environment. The use of various methods and platforms enables taking into account the students’ individual needs and preferences, which will contribute to the improvement of their speech competence and general level of knowledge.

The findings of this study have several important practical implications for language teaching, particularly for non-language-major students. As the results show, interactive online courses proved to be more effective in improving speech competence compared to traditional offline methods. This suggests that integrating online learning platforms into non-language-major curricula could enhance language acquisition in several key ways:

Non-language majors often have limited time to devote to language studies due to the demands of their primary discipline. Interactive online courses, which offer flexibility in scheduling and allow for self-paced learning, provide a practical solution. Students can fit language learning into their own schedules without the need for structured classroom sessions. This accessibility enables more consistent practice, which is critical for developing speech competence.

Online platforms like Duolingo and Rosetta Stone offer adaptive learning technologies that tailor content to the learner's individual proficiency level and progress. This is particularly valuable for non-language majors, who may come from varying linguistic backgrounds and have different needs. By allowing students to focus on areas where they need the most improvement, these tools provide a more personalized learning experience than traditional classroom settings, where instruction may not be as easily customized.

The success of online courses in this study suggests that universities could adopt **blended learning models**, where interactive online courses are used alongside traditional classroom teaching. For example, core components of speech competence, such as pronunciation drills or listening exercises, could be completed online, allowing instructors to focus on higher-level interactive activities, such as discussions or role-playing, in the classroom. This approach optimizes both time and resources, making language learning more efficient and tailored to individual students' needs.

Platforms like Duolingo, which use gamification elements such as rewards, leaderboards, and daily goals, were found to significantly increase student engagement and motivation. For non-language majors, who might not initially see the relevance of language learning to their primary field, this added layer of interaction can foster a more positive attitude toward language acquisition. Increased motivation has been consistently linked to better learning outcomes, making these platforms especially useful in keeping non-language majors invested in their language studies.

The speech competence developed through these platforms has direct applications in professional environments. Non-language majors in fields such as business, engineering, or healthcare increasingly require strong communication skills in a global context. Interactive online courses, with their emphasis on practical, everyday language use, prepare students not only for academic success but also for professional interactions. This is particularly important for students who may not pursue further formal language education but will need these skills in international or multicultural work environments.

Another practical implication of the findings is that interactive online courses can be scaled more easily than traditional classroom instruction, particularly in large universities with limited language teaching staff. By incorporating online platforms, universities can provide quality language instruction to a larger number of non-language majors without the need for significant increases in faculty or physical classroom space. Additionally, many of these platforms are cost-effective, and in some cases, free, making them a financially sustainable option for institutions looking to expand their language offerings.

The shift towards online and blended learning is in line with broader trends in higher education, where technology-enhanced learning is increasingly embraced. This study reinforces the value of such tools not only for language majors but for students across all disciplines. The implementation of online courses can also align with initiatives promoting digital literacy, self-directed learning, and lifelong learning, which are key competencies in today's rapidly changing professional landscape.

In conclusion, the integration of interactive online platforms into non-language-major curricula offers a range of benefits, from increased accessibility and flexibility to personalized learning and enhanced student motivation. By embracing these technologies, educational institutions can better equip their students with the communication skills needed for both academic and professional success in an increasingly interconnected world.

Conclusions

The growing role of distance learning urges the need to determine the effectiveness of interactive online courses for the development of speech competence of non-language-major students. The pre-and post-test results showed that they led to a marked increase in the proportion of students with higher levels of language proficiency, especially at the B2 (Upper Intermediate) level. Interactive online courses were found to be more effective in improving students’ speech competence than traditional instruction. The sample standard deviation (s) is approximately 0.45. A t value of approximately 13249 indicates a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores in the EG. It is important to note that the negative percentages (≈−50.0% and −16.7%) predict a decrease in the percentage of students at the B1 (intermediate) level after the experiment in both groups.

This may be related to the students’ transition to higher levels of language proficiency (B2, C1, etc.), and not to a decrease in the general level of language proficiency. Online courses scored higher on a Likert scale than traditional learning. Interactive online courses have been found to provide valuable opportunities for real-world language practice and interaction with native speakers, resulting in improved language skills. The user-friendly interface and capabilities of the programme, as well as the variety of topics covered, were also positively evaluated by students. Scheduling flexibility was well suited to students’ learning preferences.

The study emphasizes the advantages of interactive online courses in improving students’ speech competence. These findings can help to develop language learning programmes that incorporate these methods and identify areas to further improve students’ language learning experiences.

Research limitations

Using the OPI as a language assessment method may not fully reflect language use or performance in real life. The interview format and potential pre-examination anxiety may influence participants’ responses, which may result in differences from their actual proficiency in real-world situations. The research design reflects the level of communication competence of the participants before and after training, but cannot provide an idea of the long-term impact of interactive online courses.

Research prospects

Recommendations

It is recommended to focus on the following aspects in order to improve the effectiveness of interactive online English language courses for non-language-major students. First, personalized learning trajectories that take into account the individual needs and learning style of each student shall be actively implemented. Furthermore, it is important to systematically monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of each learning module in order to identify the most effective approaches and teaching practices. It is also necessary to actively use combined learning models to ensure a balance between online and offline activities, which will contribute to the comprehensive development of students’ speaking skills.

Bibliographic References

Albashtawi, A., & Al Bataineh, K. (2020). The effectiveness of google classroom among EFL students in Jordan: An innovative teaching and learning online platform. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(11), 78-88. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v15i11.12865

Albiladi, W. S., & Alshareef, K. K. (2019). Blended learning in English teaching and learning: A review of the current literature. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 10(2), 232-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1002.03

Ali, R., & Abdalgane, M. (2022). The impact of gamification “Kahoot app” in teaching English for academic purposes. World Journal of English Language, 12(7), 18-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v12n7p18

Baidoo-Anu, D., & Ansah, L. O. (2023). Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. Journal of AI, 7(1), 52-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.61969/jai.1337500

Bailey, D., Almusharraf, N., & Hatcher, R. (2021). Finding satisfaction: Intrinsic motivation for synchronous and asynchronous communication in the online language learning context. Education and Information Technologies, 26(3), 2563-2583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10369-z

Coman, C., Țîru, L. G., Meseșan-Schmitz, L., Stanciu, C., & Bularca, M. C. (2020). Online teaching and learning in higher education during the Coronavirus pandemic: Students’ perspective. Sustainability, 12(24), 10367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410367

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R. … & Lam, S. (2020). COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 3(1), 1-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.7

Dewaele, J. M., Chen, X., Padilla, A. M., & Lake, J. (2019). The flowering of positive psychology in foreign language teaching and acquisition research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02128

Goksu, I. (2021). Bibliometric mapping of mobile learning. Telematics and Informatics, 56, 101491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101491

González‐Lloret, M. (2020). Collaborative tasks for online language teaching. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 260-269. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12466

Gopal, R., Singh, V., & Aggarwal, A. (2021). Impact of online classes on the satisfaction and performance of students during the pandemic period of COVID 19. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 6923-6947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10523-1

Gunawan, G., Suranti, N. M. Y., & Fathoroni, F. (2020). Variations of models and learning platforms for prospective teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Indonesian Journal of Teacher Education, 1(2), 61-70. https://journal.publication-center.com/index.php/ijte/article/view/95

Gustanti, Y., & Ayu, M. (2021). The correlation between cognitive reading strategies and students’ English proficiency test score. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 2(2), 95-100.

Kasneci, E., Sessler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F. … Kasneci G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274

Kubaczka, K., & Polok, K. (2023). Effectiveness of teaching English by Quizlet to online taught 8th grade students. Society. Education. Language, 17, 125-136. https://doi.org/10.19251/sej/2023.17(8)

La Velle, L., Newman, S., Montgomery, C., & Hyatt, D. (2020). Initial teacher education in England and the Covid-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 596-608. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1803051

Lapitan J.R, L. D., Tiangco, C. E., Sumalinog, D. A. G., Sabarillo, N. S., & Diaz, J. M. (2021). An effective blended online teaching and learning strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education for Chemical Engineers, 35, 116-131. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ece.2021.01.012

Macaro, E., Curle, S., Pun, J., An, J., & Dearden, J. (2018). A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher education. Language Teaching, 51(1), 36-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000350

Murray, D. E., & Christison, M. (2019). What English language teachers need to know. Volume I: Understanding learning. New York: Routledge.

Nartiningrum, N., & Nugroho, A. (2020). Online learning amidst global pandemic: EFL students’ challenges, suggestions, and needed materials. ENGLISH FRANCA: Academic Journal of English Language and Education, 4(2), 115-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.29240/ef.v4i2.1494

Nelson, R. L., & Bonnac, M. A. (2022). How adult EFL teachers can effectively utilize Duolingo. Saint Paul: Hamline University.

Novita, D. (2021). Integrating technology and humanity into language teaching book 1: English language teaching. Yogyakarta: Deepublish.

Rojabi, A. R. (2020). Exploring EFL students' perception of online learning via Microsoft teams: University level in Indonesia. English Language Teaching Educational Journal, 3(2), 163-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.12928/eltej.v3i2.2349

Sari, F. M. (2020). Exploring English learners’ engagement and their roles in the online language course. Journal of English Language Teaching and Linguistics, 5(3), 349-361. http://dx.doi.org/10.21462/jeltl.v5i3.446

Sari, F. M., & Wahyudin, A. Y. (2019). Undergraduate students' perceptions toward blended learning through Instagram in English for business class. International Journal of Language Education, 3(1), 64-73. DOI: 10.26858/ijole.v1i1.7064

Simanjuntak, M. B., Suseno, M., Setiadi, S., Lustyantie, N., & Barus, I. R. G. R. G. (2022). Integration of curricula (Curriculum 2013 and Cambridge curriculum for junior high school level in three subjects) in pandemic situation. Ideas: Journal of Education, Social, and Culture, 8(1), 77-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.32884/ideas.v8i1.615

Tinh, D. T., Thuy, N. T., & Ngoc Huy, D. T. (2021). Doing business research and teaching methodology for undergraduate, postgraduate and doctoral students-case in various markets including Vietnam. Primary Education Online, 20(1). https://dinhtranngochuy.com/218-1612176123.pdf

Tursunovich, R. I. (2022). Guidelines for designing effective language teaching materials. American Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences, 7, 65-70. https://americanjournal.org/index.php/ajrhss/article/view/276

Zhou, L., Wu, S., Zhou, M., & Li, F. (2020). 'School’s out, but class’ on', the largest online education in the world today: Taking China’s practical exploration during The COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control as an example. Best Evid Chin Edu, 4(2), 501-519. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3555520

Zhylin, M., Mendelo, V., Cherusheva, G., Romanova, I., & Borysenko, K. (2023). Analysis of the role of emotional intelligence in the formation of identity in different European cultures. Amazonia Investiga, 12(62), 319-326. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2023.62.02.32

Este artículo está bajo la licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0). Se permite la reproducción, distribución y comunicación pública de la obra, así como la creación de obras derivadas, siempre que se cite la fuente original.