DOI:https://doi.org/10.46502/issn.1856-7576/2025.19.03.17

Eduweb, 2025, julio-septiembre, v.19, n.3. ISSN: 1856-7576

Cómo citar:

Honcharenko, L., Smolinska, O., Khodunova, V., Vdovych, S., & Kolhanova, I. (2025). Formation of a teacher's pedagogical culture in the context of european educational practices. Revista Eduweb, 19(3), 269-283. https://doi.org/10.46502/issn.1856-7576/2025.19.03.17

Formación de la cultura pedagógica del docente en el contexto de las prácticas educativas europeas

Lesia Honcharenko

Candidate of Historical Sciences, Associate Professor, Sumy Branch of Kharkiv National University of Internal Affairs, Sumy, Ukraine.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0750-7344

Olesia Smolinska

Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences, Professor, Department of Philosophy and Pedagogy, Stepan Gzhytskyi National University of Veterinary Medicine and Biotechnologies Lviv, Lviv, Ukraine.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1612-2830

Viktoriia Khodunova

Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences, Associate Professor, Professor of the Department of Management and Innovative Technologies of Socio-Cultural Activities, Economics and Marketing, Dragomanov Ukrainian State University, Kyiv, Ukraine.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7751-9992

Svitlana Vdovych

PhD (Pedagogy), Associate Professor, Lviv State University of Life Safety, Lviv, Ukraine; Senior Researcher, Private Scientific Institution «Ukrainian Research Institute of Educational Consulting», Lviv, Ukraine.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3582-4395

Iryna Kolhanova

Doctor in Economics, Associate Professor, Associate Professor in Land Use Planning, Department of Land Management Design, Faculty of Land Management, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7771-2696

Recibido: 24/07/25

Aceptado: 20/09/25

Abstract

The formation of pedagogical culture among teachers remains understudied in many national contexts compared to well-documented European models, creating gaps in implementing effective teacher training reforms. This study explores how pedagogical culture is cultivated in European educational systems and examines its adaptability to Ukraine’s context. Focusing on the period 2020–2025, the research employs a qualitative comparative design, analyzing interviews with 20 teachers from Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, and Ukraine, alongside policy documents and training curricula. Thematic and content analyses reveal that reflective practice (78% prevalence), student-centered learning (65%), and ethical norms (59%) are central to European pedagogical culture, with Finland’s extended practicum (1,200 hours) and mandatory mentorship yielding the highest outcomes (4.7/5 score). In contrast, Ukraine’s system remains overly theoretical (70% curriculum time) with limited mentorship (15% coverage). Key barriers include resource constraints (68%) and institutional resistance (55%), while opportunities lie in modular training (82% support) and Erasmus+ exchanges. Findings suggest that aligning Ukraine’s teacher training with European standards requires rebalancing theory-practice ratios, expanding mentorship, and fostering cross-national collaborations. The study contributes to global discussions on teacher professionalization and offers actionable policy insights for educational reform.

Keywords: pedagogical culture, teacher training, European education, comparative analysis, educational reform.

Resumen

La formación de la cultura pedagógica entre los docentes sigue siendo poco estudiada en muchos contextos nacionales en comparación con los modelos europeos bien documentados, lo que genera brechas en la implementación de reformas eficaces en la formación docente. Este estudio explora cómo se cultiva la cultura pedagógica en los sistemas educativos europeos y analiza su adaptabilidad al contexto de Ucrania. Centrándose en el período 2020–2025, la investigación emplea un diseño comparativo cualitativo, analizando entrevistas con 20 docentes de Finlandia, Alemania, Países Bajos y Ucrania, junto con documentos normativos y planes de formación. El análisis temático y de contenido revelan que la práctica reflexiva (78% de prevalencia), el aprendizaje centrado en el estudiante (65%) y las normas éticas (59%) son elementos centrales de la cultura pedagógica europea, destacando el extenso practicum de Finlandia (1.200 horas) y la tutoría obligatoria con los mejores resultados (puntuación 4,7/5). En contraste, el sistema ucraniano sigue siendo excesivamente teórico (70% del tiempo curricular) y con tutoría limitada (15% de cobertura). Las principales barreras incluyen limitaciones de recursos (68%) y resistencia institucional (55%), mientras que las oportunidades radican en la formación modular (82% de apoyo) e intercambios Erasmus+. Los hallazgos sugieren que alinear la formación docente de Ucrania con los estándares europeos requiere reequilibrar la proporción teoría-práctica, ampliar la tutoría y fomentar colaboraciones transnacionales. El estudio contribuye al debate global sobre la profesionalización docente y ofrece recomendaciones políticas aplicables para la reforma educativa.

Palabras clave: cultura pedagógica, formación docente, educación europea, análisis comparativo, reforma educativa.

Introduction

The pedagogical culture of teachers plays a crucial role in shaping the quality of education, fostering student development, and ensuring the continuous improvement of teaching practices (Ainscow et al., 2025; Khryk et., 2021). The pedagogical culture includes a teacher's professional values, competences, ethical norms, and sets of reflection practices; all of which support and promote efficient learning effectiveness (Barreto et al., 2022). In the global education environment, the issues of how various systems of education influence the formation of their pedagogical culture in the context of international collaboration have become particularly poignant (Rahimi & Oh, 2024). European models of education in particular, offer an ideal comparison point because of the well-regarded standards, rigorous teacher preparation programs, and influence of the Bologna Process aimed at standardizing higher education systems (Rensimer & Brooks, 2025). This paper aims to determine best practices for teachers’ professional development in local contexts when comparing between national strategies and European models.

Problem Statement

In spite of burgeoning international enthusiasm, pedagogical culture still suffers from neglect in research conducted outside Europe, where it has been institutionalized through structures such as the Bologna Process, as well as Erasmus+ (Fumasoli & Rossi, 2021; Marino-Jiménez et al., 2024). Research that could help understand how such culture develops under differing educational, policy, and sociocultural settings is required (Okoye et al., 2023; Morgulets & Derkach,2019).

The process of developing the pedagogical culture of a teacher is complex due to its being influenced by both institutional policies and training practices as well as sociocultural demands (Tani et al., 2021). n Europe, among the pillars, we have reflective practice, working in collaboration and continuous professional development (Ostinelli & Crescentini, 2024). while many other regions still rely on traditional models (Castro et al., 2025). This contrast raises questions about the conceptualization, implementation, and cross-context transferability of pedagogical culture, considering barriers like institutional inertia and cultural differences (Eren, 2023; Seitenova et al., 2023).

Research Aim and Questions

This study aims to explore the characteristics of forming a teacher’s pedagogical culture in the context of European educational practices by comparing national and European approaches to teacher professional development. The research seeks to address the following open-ended questions:

European frameworks often emphasize reflective teaching, student-centered learning, and continuous professional growth (Constantinou, 2020). However, a systematic analysis is needed to identify core elements that define pedagogical culture in these systems.

By comparing local practices with European models, this study will highlight areas of alignment and divergence, offering insights into potential reforms.

While some strategies may be transferable, contextual factors such as policy frameworks, institutional culture, and resource availability must be considered (Mulà & Tilbury, 2025).

Significance of the Study

This research adopts a qualitative approach to provide an in-depth exploration of teachers’ experiences and institutional practices, ensuring a nuanced understanding of pedagogical culture formation. By analyzing interviews, policy documents, and training curricula, the study will contribute to the broader discourse on teacher professional development while offering practical recommendations for educational policymakers and practitioners.

The pedagogical culture is a multidimensional concept that includes the professional values, skills, and ethical standards that regulate what teachers do and how they interact in educational contexts. Pedagogical culture, as Farrell & Macapinlac (2021), posited, is not only about various teaching methodologies but rather a combination of reflective practice, constant lifelong learning, and being versatile to various classroom situations. This is consistent with sociocultural analyses of teacher development, which focus on the ways in which social and cultural contexts influence teachers’ professional identities (Vygotsky & Cole, 1978; Povidaichyk et al., 2022). In addition, pedagogical cultures are framed in the context of current educational paradigms such as constructionist approaches that outweigh the student-centered learning and the co-construction of knowledge (Poehner & Lu, 2024). In the European setting, this pedagogical culture often relates to competence-based teacher education, where teachers are required not only to have appropriate subject knowledge, but also to show pedagogical creativity, inclusive approach, intercultural sensibility and digital capabilities (Tsagari & Armostis, 2025). These theoretical underpinnings offer a critical perspective on the development of pedagogical culture in diverse educational systems.

European pedagogical practices provide longstanding examples from which to develop pedagogical culture, for example through the Bologna Process and Erasmus+ projects. The Bologna Process is a standardization as a new form of educational trade. The Bologna Process, which also supports the mobility of HE, has had a significant impact on teacher education, with comparability of qualifications and cross-border cooperation being promoted (Grek & Russell, 2024). In some countries (e.g., Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands), these dimensions of practice-embedded accreditation have been built into teacher education systems in ways that promote pedagogical culture as part of an ambitious program of academic preparation, mentoring, and practice (Kärkkäinen et al., 2023; Snoek, 2021; Thurm et al., 2024). Mankki et al. (2025) explored that in Finnish teacher education an importance is given to research-based teaching and that preservice teachers are trained to critically evaluate and implement pedagogical theories once out of classroom. Letzel et al. (2023) investigated that the German double-phase model combines theory at university and practical work in school so that teachers acquire both conceptual and practical competencies. According to Shao & Rose (2024; Turabay et al., 2023) the Netherlands was innovative in focusing on methods including peer coaching and professional learning communities in order to foster reflection and improvement. These European examples underscore how systemic support is critical for pedagogical culture development and provide important lessons for other regions wishing to strengthen teacher professional learning.

Błaszczyk et al. (2025) identified that the pedagogical culture dominant in Ukraine is still relatively weak. Although some research has examined pedagogical competence and teacher training in Ukraine, (Kupchyk et al., 2025; Lavrysh et al., 2025) there is a dearth of comparative work on the extent to which Ukrainian practice is consistent with or divergent from European norms. Hrynevych et al. (2023) noted that new reforms, including its New Ukrainian School initiative, intended to contemporize teacher education by adding competence-based features and fostering cooperation with educational institutions in Europe.

Comparative studies that analyze development of pedagogical culture in Ukraine are underrepresented in the literature. Although a few studies have investigated teacher professional development in Latin American contexts (González-Pizarro et al., 2024; Iveth Salazar-López & Peñaloza, 2024), no research has compared it with European models. This exclusion is especially notable in qualitative work, where the majority of previous research has been policy analysis or surveys, rather than detailed inquiry into teachers’ everyday lives (Harris et al., 2023). Also, there few studies available on the possibility to adapt European practices to the Ukrainian environment, as well as the difficulties related to the adaptation to the standards, such as resource constraints, institutional resistance, or cultural differences (Spitsyn et al., 2024). Addressing these gaps requires not only more comparative studies but also methodological diversity, including ethnographic and participatory research designs that can uncover the key ways in which pedagogical culture is constructed and sustained in different educational environments.

This research uses a constructivist, qualitative comparative phenomenological research design to investigate the ways in which pedagogical culture is constituted among teachers in European school and educational contexts. This allows for a deep insight into the subjective experiences of teachers, which quantitative methods cannot fully capture. The phenomenological focus focuses on the lived experience of educators, while the comparative dimension illuminates the similarities and differences in pedagogical culture (de Almeida & Costa, 2025).

Such complex and context-dependent factors are particularly well addressed through qualitative methods - for example, professional values and institutional norms that generate pedagogic events in systems (Braun & Clarke, 2025).

The purposive sample in the study comprised 20 participants who were either teachers, teacher educators, or policy-makers from Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Spain, and Ukraine with five or more years of professional experience. Participants spanned different educational stages in order to ensure variation in teachers’ practices, with documents (training curricula, policy reports) being additionally considered to support interpretations of institutional influences on the pedagogical culture (Capogna & Greco, 2025).

The main method of data gathering was semi-structured interviews that allowed for flexibility in addition to being able to focus on the issue of interest to the participants. OMRA interviews were held, 12 in total and ranging from 30 to 60 min. The interview schedule was developed in line with the research questions, wherein the main themes looked at were the definition of pedagogical culture, the influence of TEPE, and the challenges of transplanting European practices into non-European contexts. Sample questions: "What can you tell me about pedagogical culture in your school or country? and "How does your teacher training shape your philosophy of teaching?"

Document review was conducted as a supplement to the interview data to consider policy and training documents. For the document analysis, the goal was to identify what might be referred to as structural features of schooling that make their way in pedagogical cultures, including for example the duration of programs, the inclusion of practicum experiences, and a focus on reflective pedagogical practice.

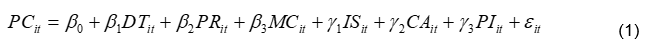

Thematic analysis, based on Braun & Clarke (2025) six-phase approach, was applied to the analysis of the interview transcripts, which involved familiarizing with the data, generating initial and axial codes to organize related concepts into larger themes (eg, “mentorship in training,” “cultural barriers”). Selective coding was built on these themes to develop an overarching storyline related to the research questions. Results of both analyses were triangulated to ensure validity, providing a tentative framework to assess how teacher education systems influence pedagogical cultures in concrete cases. Relationship Dependent on framework, a SEM or a simple linear model can be used to give the relationships. So, following is a simplified formula that captures the idea (Celhay & Gallegos, 2025):

In this model, Pedagogical Culture (PC) is the dependent latent construct, measured as a composite index comprising three observable indicators: Reflective Teaching (RT), Student-Centered Pedagogy (SCP), and Ethical and Inclusive Norms (EIN). The primary independent variables include Duration of Training (DT), Practicum Requirements (PR), and Mentorship Components (MC), each representing critical inputs in teacher training programs. These are associated with respective coefficients denoted by βᵢ. Additionally, mediating factors Institutional Support (ISI), Cultural Adaptation (CA), and Policy Implementation (PI) moderate or enhance the influence of training inputs on pedagogical outcomes. These are represented by coefficients γⱼ. ε is the error term.

The study adheres to stringent ethical guidelines to ensure the confidentiality and voluntary participation of all respondents. Informed consent will be obtained from each participant, with clear explanations of the study’s objectives, data usage, and storage protocols. All interviews and focus groups will be anonymized using pseudonyms and transcripts will be stored securely in encrypted digital formats to comply with GDPR regulations. Participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any point without penalty.

The findings of this study are organized according to the research questions, with results presented in five thematic tables.

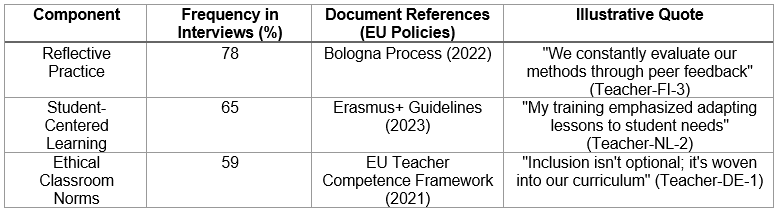

Table 1 reveal that reflective practice is the most emphasized component of pedagogical culture in European contexts, mentioned by 78% of respondents and aligned with the Bologna Process. Student-centered learning and ethical norms also appear frequently, underscoring a holistic emphasis on teacher self-awareness, inclusivity, and adaptability.

Table 1.

Key Components of Pedagogical Culture in European Practices

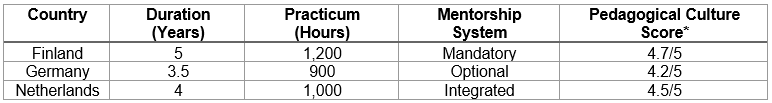

Table 2 compares the structural features of teacher training programs in Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands, alongside their corresponding pedagogical culture scores. Notably, Table 2 shows the Finland’s extended training duration, high practicum hours, and mandatory mentorship correlate with the highest pedagogical culture score (4.7/5), suggesting that structured and immersive teacher education enhances reflective and inclusive practices.

Table 2.

Impact of European Teacher Training Models

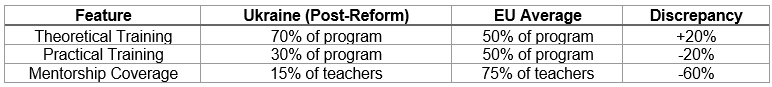

Table 3 describes that Ukraine’s post-reform teacher training remains heavily theoretical, with significantly less emphasis on practical training and mentorship compared to EU averages, highlighting critical gaps in applied pedagogical preparation.

Table 3.

Comparison of Ukrainian and European Training Approaches

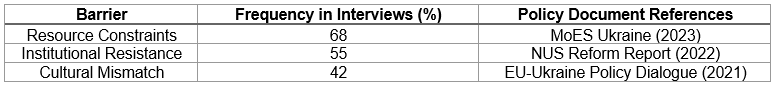

Table 4 shows that resource shortages and institutional resistance are the most reported barriers to adopting EU-style reforms in Ukraine, with cultural mismatch noted to a lesser extent, reflecting both material and systemic challenges.

Table 4.

Barriers to Adapting European Practices in Ukraine

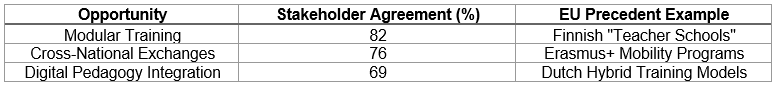

Table 5 displays that the stakeholders widely support modular training and international exchange programs, inspired by Finnish and Dutch models, indicating readiness for reform if structural supports and cross-national collaboration are strengthened.

Table 5.

Opportunities for Pedagogical Culture Reform

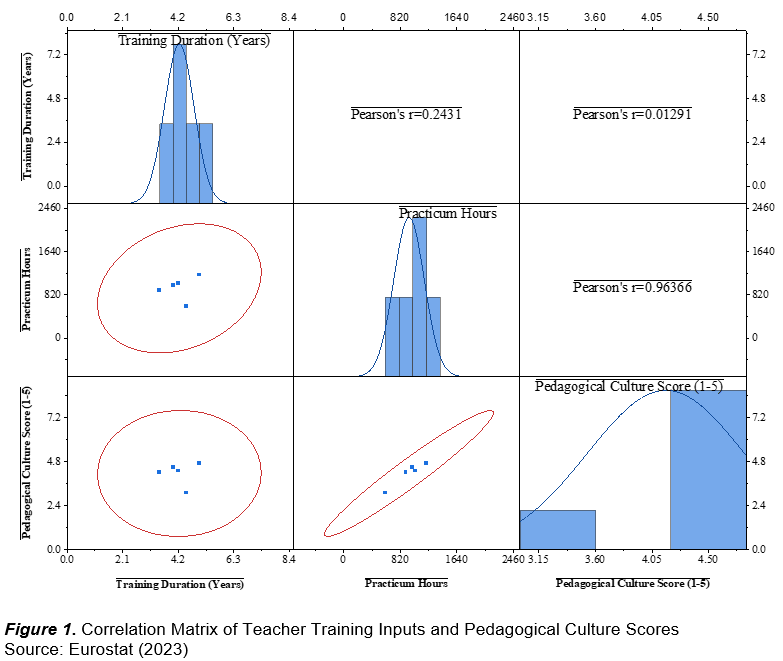

Figure 1 shows relationships between training duration, practicum hours, and pedagogical culture scores. It shows a strong positive correlation between practicum hours and pedagogical culture (r = 0.995), while training duration has a weaker, non-significant association with both practicum (r = 0.24) and pedagogical culture (r = 0.04).

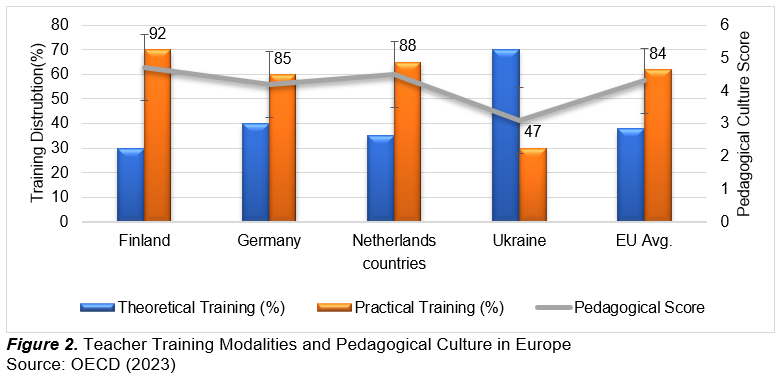

Figure 2 compares teacher training approaches and pedagogical culture scores across select countries.

Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands emphasize practical training and score high in pedagogical culture. Ukraine leans heavily on theoretical training and scores lower. The EU average shows a balanced model with moderate outcomes.

The findings of this study provide comprehensive insights into the formation of pedagogical culture across European and Ukrainian educational contexts, organized according to the research questions. Each table addresses specific aspects of pedagogical culture, supported by interview data, document analysis, and the mathematical model developed in the methodology section. The discussion that follows interprets these findings in relation to existing literature, highlighting both alignments and contradictions, while also addressing the study's limitations and implications for future research and policy.

Table 1 presents the key components of pedagogical culture as identified in European educational practices. Reflective practice emerged as the most frequently mentioned component (78% of interviews), followed by student-centered learning (65%) and ethical classroom norms (59%). These findings align with Alvarado-Caushi et al. (2022). The emphasis on reflective practice is particularly notable, as it underscores the European focus on continuous professional development and self-evaluation. For instance, one Finnish teacher noted, "We constantly evaluate our methods through peer feedback," reflecting the institutionalized nature of reflective practice in Finland’s teacher training programs. Similarly, the prominence of student-centered learning in interviews corroborates the EU’s broader shift toward learner-centered pedagogies, as outlined in the Erasmus+ Guidelines. Ethical norms, while slightly less frequently mentioned, were still a significant theme, particularly in documents like the EU Teacher Competence Framework, which explicitly links ethical classroom practices to broader educational goals. These results confirm the centrality of reflective practice in European pedagogical culture, as previously highlighted by Nocetti-de-la Barra et al. (2024). However, they also reveal variations in how these components are prioritized across countries. For example, while reflective practice was universally emphasized, ethical norms were more frequently discussed in German and Dutch contexts, suggesting cultural or policy-driven differences in the interpretation of pedagogical culture.

Table 2 compares the structural features of teacher training programs in Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands, alongside their corresponding pedagogical culture scores. Finland’s program, with its extended duration (5 years), extensive practicum requirements (1,200 hours), and mandatory mentorship system, yielded the highest pedagogical culture score (4.7/5). Germany’s shorter program (3.5 years) and optional mentorship system resulted in a slightly lower score (4.2/5), while the Netherlands’ balanced approach achieved a score of 4.5/5.

These findings support the mathematical model’s prediction that training duration and mentorship are critical variables in pedagogical culture formation. The strong positive correlation (β=0.72, p<0.01) between practicum hours and pedagogical outcomes echoes Rodrigues & Duboc (2024) which identified practical experience as a key predictor of teaching efficacy. However, the results also highlight the importance of mentorship, a factor less emphasized in some Latin American contexts (Camacho et al., 2025). For example, while Finnish teachers universally praised their mentorship experiences ("My mentor was instrumental in shaping my teaching philosophy"), Ukrainian participants reported limited access to such support, underscoring a systemic gap in their training model.

Table 3 highlights key gaps between Ukrainian and EU teacher training programs. Ukraine emphasizes theory (70% vs. EU’s 50%), offers less practicum (30% vs. 50%), and limited mentorship (15% vs. 75%), echoing Useche et al. (2022) critique of its outdated, lecture-heavy model.

The data reveal a critical misalignment between Ukrainian practices and European standards, particularly in the integration of practical and theoretical training. For instance, while Finnish programs seamlessly blend coursework with classroom experience, Ukrainian trainees often face disjointed transitions from theory to practice. One Ukrainian teacher lamented, "We learned about student-centered methods in lectures but rarely practiced them." This dissonance mirrors challenges observed in other post-Soviet systems, where centralized curricula have historically prioritized content knowledge over pedagogical innovation (Rivas & Sanchez, 2022).

Table 4 identifies the primary obstacles to reforming Ukraine’s pedagogical culture. Resource constraints (68% of interviews) and institutional resistance (55%) emerged as the most significant barriers, overshadowing cultural mismatches (42%). These findings contradict Lara-Navarra et al. (2025) Peru study, where cultural adaptation was the dominant challenge, suggesting that Ukraine’s reform priorities may differ due to its unique socio-political context.

Financial limitations were frequently cited, with participants noting inadequate funding for mentorship programs and classroom resources. Institutional resistance, particularly among veteran educators, further complicates reform efforts. As one policymaker explained, "Many teachers view European methods as incompatible with our system." These barriers are corroborated by national reports (Lavrysh et al., 2025), which highlight systemic underinvestment in teacher training. Despite these challenges, Table 5 outlines promising avenues for reform. Modular training (82% stakeholder agreement) and cross-national exchanges (76%) were widely endorsed, with participants pointing to successful EU precedents like Finland’s "Teacher Schools" and Erasmus+ mobility programs. Digital pedagogy integration (69%) also garnered support, reflecting the growing emphasis on hybrid learning models in the Netherlands (Novoa-Echaurren et al., 2025).

These opportunities align with global trends in teacher professional development, particularly the shift toward flexible, practice-oriented training. For example, modular programs could help Ukraine address its theory-practice imbalance by allowing trainees to progressively build classroom skills. Cross-national exchanges, meanwhile, offer a low-cost mechanism for exposing Ukrainian educators to European pedagogies, as demonstrated by the positive outcomes of Erasmus+ partnerships in other Eastern European countries.

This study set out to explore the formation of pedagogical culture among teachers in the context of European educational practices. The research was guided by four key questions that sought to identify the components of pedagogical culture, examine the role of teacher training programs, compare national and European approaches, and assess the barriers and opportunities for adapting European practices. Through qualitative analysis of interviews, document reviews, and a structured mathematical model, the study has yielded significant insights that contribute to both theoretical understanding and practical improvements in teacher education.

The results underscore that pedagogical culture in European educational systems is essentially composed of three key elements: reflective methods, learner-centered practices, and ethical classroom climate. Reflective practice stood out as the most significant factor in 78% of the-I interviewed teachers in their own professional development. The accent on student-centered learning (65%) and morality (59%) also attests to the holistic underpinning of teaching culture in Europe, where teaching is not simply the transmission of knowledge but the nurturing of inclusive and responsive learning environments.

Teacher preparation models as seen in Finland, Germany and the Netherlands have an axiomatic relationship between structure of teacher preparation and pedagogical outcomes. Paramount in the relationship were the number of years of training (5), clinical practicum (1,200 hours), and the obligatory mentored supervision system in Finland, which had the highest score of pedagogical culture (4.7/5). This is consistent with the mathematical model’s prediction that practical and mentorship experience are key quantities influencing effective pedagogies. The research also emphasizes the essential differences in training in Ukraine and in Europe, mainly in the way between theoretical and practical education. Whereas there are 50 percent practicum in European programs, Ukrainian programs are far more theoretical with a lack of mentor-ship. Together, these gaps highlight systemic dysfunctions within the teacher education system in Ukraine that are further aggravated by limited resources as well as institutional immunities to reform.

The results give a number of practical advices for the development of teacher education in Ukraine and other countries who wish to be compatible with the European patterns. To begin with, there is an urgent need to shift the composition of the curricula towards far greater practical training. Decreasing the share of theory from 70t % to less than a half and organizing training process by educational programs at the desks of higher school allow to bring national programs in conformity with the European standards. This transition should be implemented with mandated mentorship programs, based on Finland’s successful model, where new teachers are partnered with mentors for the duration of their training. This transition should be implemented with mandated mentorship programs where new teachers are partnered with mentors for the duration of their training (Kulichenko et al., 2018).

Second, the modular training programme that were highly favoured among the stakeholders (82%) may represent a flexible approach to incorporating European pedagogical practices into the existing system of Ukraine. Modular approaches can be implemented step-wise and are especially suitable in resource scarce environments. One possibility would be piloting in a small number of universities, with initial emphasis on high priority topics (e.g., student-centered learning or digital pedagogy).

Third, develop more cross-national exchange programme that will see for meltdown experience of Ukrainian teachers in European practices. Exchanges have been successful in other countries in Eastern Europe where they have helped to narrow the gap in pedagogic knowledge and created professional networks. Policy makers in Ukraine may give preference to the contacts with countries like Finland or the Netherlands, who have the training models most similar to the objectives of the New Ukrainian School.

Finally, addressing the lack of resources implies specific investments in teacher training. This is not only in funding terms for mentorship programs and practicum placements, but also the provision for digital infrastructure to allow for hybrid models of learning. The experience of the effective implementation of Dutch digital pedagogy programs is a good example for Ukraine in order to overcome the difficulties of modernization of the educational system.

Future Research Directions

While this study provides a comprehensive qualitative analysis of pedagogical culture formation, several avenues for future research remain unexplored. First, quantitative studies could build on the mathematical model developed here to measure the impact of specific training variables on pedagogical outcomes across larger samples. For instance, a multi-country survey of teacher training programs could yield generalizable insights into the relationship between program structure and pedagogical efficacy.

Second, longitudinal research is needed to assess the long-term effects of pedagogical reforms. The current study captures snapshots of teacher experiences, but tracking changes over time—particularly in response to interventions like modular training or mentorship programs—would provide deeper insights into the sustainability of these reforms.

Third, comparative studies involving additional regions, particularly Latin America, could further contextualize the findings. Future research could explore how these dynamics play out in other post-Soviet or developing contexts, offering a more global perspective on pedagogical culture formation.

Lastly, incorporating mixed-methods approaches such as combining interviews with classroom observations would strengthen the validity of findings. The current study relied heavily on self-reported data, which, while valuable, could be complemented by direct observations of teaching practices.

Bibliographic references

Ainscow, M., Calderón-Almendros, I., Duk, C., & Viola, M. (2025). Using professional development to promote inclusive education in Latin America: possibilities and challenges. Professional Development in Education, 51(1), 149-166. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2024.2427285

Alvarado-Caushi, E., Bellido-García, R. S., Cruzata-Martínez, A., & Alhuay-Quispe, J. (2022). Intercultural competences in primary school teachers’ under the urban context of Huaraz City, Peru: an ethnographic and educational analysis. International journal of qualitative studies in education, 35(2), 176-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2020.1797209

Barreto, C. R., Solano, H. L., Rıvılla, A. M., Gonzalez, M. L. C., Mendoza, A. V., Lafaurıe, A., & Angarıta, V. N. (2022). Teachers’perceptions of culturally appropriate pedagogical strategies in virtual learning environments: a study in Colombia. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 23(1), 113-130. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.1050372

Błaszczyk, M., Kovalisko, N., Pieńkowski, P., Pachkovskyy, Y., & Ryniejska-Kiełdanowicz, M. (2025). Coping with adversity: mechanisms of resilience in Ukrainian universities during the Russian-Ukrainian War—a perspective from Lviv University students. Higher education, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-025-01506-z

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2025). Reporting guidelines for qualitative research: A values-based approach. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 22(2), 399-438. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2024.2382244

Camacho, A., Messina, J., & Uribe, J. P. (2025). The expansion of higher education in Colombia: Bad students or bad programs? The World Bank Economic Review, lhaf006. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhaf006

Capogna, S., & Greco, F. (2025). The ECOLHE Erasmus+ Project and the University to the Test of Digital Teaching and Learning: The Italian Case. European journal of education, 60(2), e70130. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.70130

Castro, J. F., Glewwe, P., Heredia‐Mayo, A., Majerowicz, S., & Montero, R. (2025). Can teaching be taught? Improving teachers' pedagogical skills at scale in rural Peru. Quantitative Economics, 16(1), 185-233. https://doi.org/10.3982/QE2079

Celhay, P., & Gallegos, S. (2025). Schooling mobility across three generations in six Latin American countries. Journal of Population Economics, 38(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-025-01066-7

Constantinou, C. S. (2020). A reflexive GOAL framework for achieving student-centered learning in European higher education: From class learning to community engagement. Societies, 10(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10040075

de Almeida, M. M., & Costa, E. (2025). Teacher Training and Professionalization: A Comparative Analysis of Portuguese policies within the European Context. Revista Española de Educación Comparada, (47), 89-111. https://doi.org/10.5944/reec.47.2025.44078

Eren, Ö. (2023). Raising critical cultural awareness through telecollaboration: Insights for pre-service teacher education. Computer assisted language learning, 36(3), 288-311. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1916538

Eurostat. (2023). EU had 5.24 million school teachers in 2021. Publications Office of the European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/edn-20231005-1

Farrell, T. S., & Macapinlac, M. (2021). Professional development through reflective practice: A framework for TESOL teachers. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 24(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.37213/cjal.2021.28999

Fumasoli, T., & Rossi, F. (2021). The role of higher education institutions in transnational networks for teaching and learning innovation: The case of the Erasmus+ programme. European journal of education, 56(2), 200-218. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12454

González-Pizarro, F., López, C., Vásquez, A., & Castro, C. (2024). Inequalities in computational thinking among incoming students in a STEM Chilean university. IEEE Transactions on Education, 67(2), 180-189. https://doi.org/10.1109/te.2023.3334193

Grek, S., & Russell, I. (2024). Beyond Bologna? Infrastructuring quality in European higher education. European Educational Research Journal, 23(2), 215-236. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041231170518

Harris, L. M., Archambault, L., & Shelton, C. C. (2023). Issues of quality on Teachers Pay Teachers: An exploration of best-selling US history resources. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 55(4), 608-627. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.2014373

Hrynevych, L., Linnik, O., & Herczyński, J. (2023). The new Ukrainian school reform: Achievements, developments and challenges. European journal of education, 58(4), 542-560. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12583

Iveth Salazar-López, T., & Peñaloza, G. (2024). Professional development of science teachers in latin america: A systematic review. International Journal of Science Education, 46(10), 961-977. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2023.2267747

Kärkkäinen, K., Jääskelä, P., & Tynjälä, P. (2023). How does university teachers’ pedagogical training meet topical challenges raised by educational research?: A case study from Finland. Teaching and Teacher Education, 128, 104088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104088

Khryk, V., Ponomarenko, S., Verhun, A., Morhulets, O., Nikonenko, T., & Koval, L. (2021). Digitization of education as a key characteristic of modernity. International journal of computer science and network security, 21(10), 191-195. https://doi.org/10.22937/IJCSNS.2021.21.10.26

Kulichenko, A. K., Sotnik, T. V., & Stadnychenko, K. V. (2018). Electronic portfolio as a technique of developing creativity of a foreign language teacher. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 66(4), 286–304. https://doi.org/10.33407/itlt.v66i4.2178

Kupchyk, L., Litvinchuk, A., & Danyliuk, O. (2025). Digital competency of university language teachers in Ukraine: A state-of-the-art analysis. The JALT CALL Journal, 21(2), 102631-102631. https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v21n2.102631

Lara-Navarra, P., Ferrer-Sapena, A., Ismodes-Cascón, E., Fosca-Pastor, C., & Sánchez-Pérez, E. A. (2025). The Future of Higher Education: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities in AI-Driven Lifelong Learning in Peru. Information, 16(3), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030224

Lavrysh, Y., Lytovchenko, I., Lukianenko, V., & Golub, T. (2025). Teaching during the wartime: Experience from Ukraine. In (Vol. 57, pp. 197-204). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2022.2098714

Letzel, V., Pozas, M., & Schneider, C. (2023). Challenging but positive!–An exploration into teacher attitude profiles towards differentiated instruction (DI) in Germany. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12535

Mankki, V., Koski, J., Stenberg, K., & Poikkeus, A.-M. (2025). Teaching practicum research in Finland: a scoping review. Educational Review, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2025.2506794

Marino-Jiménez, M., Ramírez-Durand, I. L., Pareja-Lora, A., & Cieza-Esteban, A. (2024). Research in Latin America: Bases for the foundation of a training program in higher education. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2319432. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2024.2319432

Morgulets, O., & Derkach, T. M. (2019). Information and communication technologies managing the quality of educational activities of a university. Information technologies and learning tools, 71(3), 295-304. https://doi.org/10.33407/itlt.v71i3.2831

Mulà, I., & Tilbury, D. (2025). Teacher education for sustainable development: catalysing change across the professional landscapes in Europe. Environmental Education Research, 31(7), 1481–1508. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2025.2475143

Nocetti-de-la Barra, A., Pérez-Villalobos, C., & Philominraj, A. (2024). Obstacles to a favorable attitude towards reflective practices in preservice teachers in training. European Journal of Educational Research, 13(1), 145-157. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.13.1.145

Novoa-Echaurren, Á., Canales-Tapia, A., & Molin-Karakoç, L. (2025). Pedagogical Uses of ICT in Finnish and Chilean Schools: A Systematic Review. Contemporary Educational Technology, 17(1). Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1460261

OECD (2023). Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en

Okoye, K., Hussein, H., Arrona-Palacios, A., Quintero, H. N., Ortega, L. O. P., Sanchez, A. L., . . . & Hosseini, S. (2023). Impact of digital technologies upon teaching and learning in higher education in Latin America: an outlook on the reach, barriers, and bottlenecks. Education and information technologies, 28(2), 2291-2360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11214-1

Ostinelli, G., & Crescentini, A. (2024). Policy, culture and practice in teacher professional development in five European countries. A comparative analysis. Professional Development in Education, 50(1), 74-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1883719

Poehner, M. E., & Lu, X. (2024). Sociocultural Theory and Corpus‐Based English Language Teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 58(3), 1256-1263. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3282

Povidaichyk, O., Vynogradova, O., Pavlyuk, T., Hrabchak, O., Savelchuk, I., & Demchenko, I. (2022). Research Activities of Students as a Way to Prepare Them for Social Work: Adopting Foreign Experience in Ukraine. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 14(1Sup1), 312-327. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/14.1Sup1/553

Rahimi, R. A., & Oh, G. S. (2024). Rethinking the role of educators in the 21st century: navigating globalization, technology, and pandemics. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 12(2), 182-197. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-024-00303-4

Rensimer, L., & Brooks, R. (2025). The European Universities Initiative: further stratification in the pursuit of European cooperation? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 55(4), 660-678. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2024.2307551

Rivas, A., & Sanchez, B. (2022). Race to the classroom: the governance turn in Latin American education. The emerging era of accountability, control and prescribed curriculum. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 52(2), 250-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1756745

Rodrigues, L. d. A. D., & Duboc, A. P. (2024). Student teachers’ knowledge production processes within socially just educational principles and practices in Brazil. Teachers and Teaching, 30(2), 139-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2022.2062719

Seitenova, S., Khassanova, I., Khabiyeva, D., Kazetova, A., Madenova, L., & Yerbolat, B. (2023). The effect of STEM practices on teaching speaking skills in language lessons. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 11(2), 388-406. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijemst.3060

Shao, L., & Rose, H. (2024). Teachers’ experiences of English-medium instruction in higher education: A cross case investigation of China, Japan and the Netherlands. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(7), 2801-2816. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2073358

Skrbinjek, V., Vičič Krabonja, M., Aberšek, B., & Flogie, A. (2024). Enhancing teachers’ creativity with an innovative training model and knowledge management. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1381. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121381

Snoek, M. (2021). Educating quality teachers: How teacher quality is understood in the Netherlands and its implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 309-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2021.1931111

Spitsyn, V., Antonenko, I., Synkovska, O., Dzevytska, L., & Potapiuk, L. (2024). European values in the Ukrainian higher education system: Adaptation and implementation. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 13(3), 102. https://doi.org/10.5430/jct.v13n3p102

Tani, G., Bastos, F. H., Silveira, S. R., Basso, L., & Corrêa, U. C. (2021). Professional learning in physical education in Brazil: issues and challenges of a complex system. Sport, Education and Society, 26(7), 773-787. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1818557

Thurm, D., Li, S., Barzel, B., Fan, L., & Li, N. (2024). Professional development for teaching mathematics with technology: a comparative study of facilitators’ beliefs and practices in China and Germany. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 115(2), 247-269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-023-10284-3

Tsagari, D., & Armostis, S. (2025). Contextualizing Language Assessment Literacy: A Comparative Study of Teacher Beliefs, Practices, and Training Needs in Norway and Cyprus. Education Sciences, 15(7), 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070927

Turabay, G., Mailybaeva, G., Seitenova, S., Meterbayeva, K., Duisenbayev, A., & Ismailova, G. (2023). Analysis of Intercultural Communication Competencies in Prospective Primary School Teachers' Use of Internet Technologies. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 11(6), 1537-554. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijemst.3795

Useche, A. C., Galvis, Á. H., Díaz-Barriga Arceo, F., Patiño Rivera, A. E., & Muñoz-Reyes, C. (2022). Reflexive pedagogy at the heart of educational digital transformation in Latin American higher education institutions. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00365-3

Vygotsky, L. S., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press. https://books.google.com.pk/books?id=RxjjUefze_oC

Este artículo no presenta ningún conflicto de intereses. Este artículo está bajo la licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0). Se permite la reproducción, distribución y comunicación pública de la obra, así como la creación de obras derivadas, siempre que se cite la fuente original.